Horse Training Tips

A Grand Meadows Special Interview with horse trainer, certified riding instructor, and Author Lynn Acton

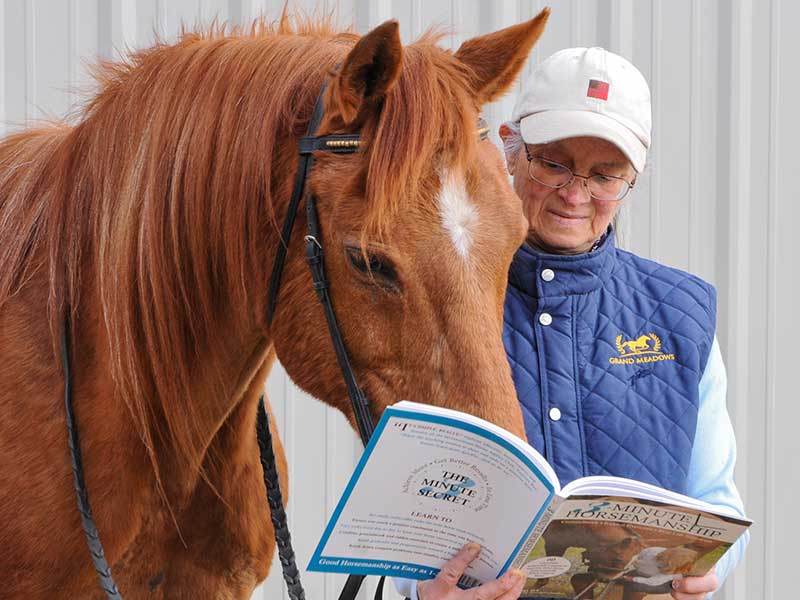

Meet Lynn Acton, the author of What Horses Really Want

It is part of our mission at Grand Meadows to connect the Grand Meadows community with experts in horse behavior, wellness, and training. We believe these connections make it easier for everyone to learn about horse heath, wellness, and care.

This month we have a feature interview with Lynn Acton. Some of you may know Lynn from her popular website and Facebook page where she shares articles and resources about:

- Horse Agility

- Horse Communication and Leadership

- Confidence Building

- Healthy Horse Keeping

- History

- Horse Behavior and Herd Dynamics

- Horses and Children

- Riding and Training

Lynn’s mission is to advocate for horses and try to understand their point of view. She strives to answer key questions about what matters to horses, how to best communicate with them, and what motivates horses. With this information, Lynn believes horse riders of all ages and experience levels are better at improving their horse’s welfare, staying safe, and pursuing riding and training goals.

We sat down with Lynn to ask her about herself, horses, her book, and what horses really want.

Q. How did you get involved with horses?

Lynn: I was obsessed from the time I knew what a horse was, and always read everything I could find. At 12, I started earning riding privileges by doing chores for a horse dealer. It was a unique education. Most of the horses stayed for at least a few months, so we got to know them. As my skills developed, I worked with those who had behavior problems, focusing on the safe behaviors that help horses find and keep good homes.

Q. How do you approach teaching and working with your students?

Lynn: I encourage riders to have two-way conversations with their horses so they are not just giving instructions, but also reading the horse’s feedback. Often instructors say, “Do this, and the horse will do that.” Then if it doesn’t work, the rider feels like either they did something wrong or their horse did – not a good atmosphere for learning. Instead I say, “Try this and tell me what happens.” Experimenting encourages riders to listen to their horses and come up with a new plan if the first one didn’t work.

Since I teach mainly people who have their own horses, the dynamics between horse and human are especially important. Often when people think their horse has a behavior problem, it is really a communication issue that can be solved quickly with clearer body language on the ground or clearer, gentler riding cues. Good balance is also crucial since aligning ourselves with horses’ center of gravity helps them carry us most comfortably.

Q. What inspires you to write about horse behavior and advocate for horse welfare?

Lynn: I have always felt that horses were smarter, gentler, and more cooperative than they get credit for. The way we treat them becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. When we assume that horses want to be good partners, we find ways to make that happen. People who expect horses to be stupid, resistant, or aggressive provoke the behaviors they expect.

Q. What inspired you to write What Horses Really Want?

Lynn: My horses did, especially Brandy, my “cover girl”. She came to me so fearful she was dangerous. Her previous trainer had used dominance-based methods that back-fired badly, so I had nothing to lose by trying a radically different approach.

I focused less on obedience, and more on helping Brandy feel safe with me. Soon she was coming when I called her, running to me when she was scared, and competing in horse agility. Her trust transferred to other people. Now she does agility with my grandchildren, carefully watching out for them.

Research told me that my make her feel safe approach has been used successfully for centuries, but hardly anyone explained how to do it. There is no drama in it, and no special gear to buy. It’s not a training system – it is a relationship built on trust.

I call it Protector Leadership because being the horse’s protector is what makes it work. I wanted to describe it in a way that anyone can do it, starting the minute you meet a horse.

Q. Tell me about your other horses. Did you change the way you related to them?

Lynn: Yes, and we saw positive changes in each one. Bronzz, my zany Arabian, is supremely self-confident. He has never been treated badly, never been a behavior problem. But as I got quieter and more patient, he acted happier to see me and more interested in hanging out with me. My husband’s mare Shiloh became less tense and reactive.

However, the biggest change was in our older palomino Sapphire, a “dominant” mare who had scared people everywhere she lived. As I got less bossy, she got less defensive, and more cooperative. We saw that her dominance was more like bravado covering up sensitivity and anxiety.

Q. Can you tell us about how you use Grand Meadows horse supplements with your horses?

Lynn: It was Sapphire who led me to discover Grand Hoof. She had such terrible, crumbly hooves, we almost had to retire her when she was only 20. I tried several reputable hoof supplements with no luck. The magic formula was Grand Hoof with a multivitamin supplement, and of course excellent farrier care. Seven more years of riding, seven years of retirement, and Sapphire was still galloping around the week before she passed away from a stroke at age 34.

I started Bronzz on Grand Hoof as part of his recovery from laminitis. It has been a standard part of his diet, and Shiloh’s ever since. Bronzz’s hooves have stayed healthy and sound through all our adventures: dressage musical freestyles, trail trials, countless trail rides, and Equagility (ridden agility) competitions through the International Horse Agility Club. In 2018 he was Equagility World Champion. At age 25 he is Insulin Resistant and PPID, but there is still a bounce in his step.

I didn’t give Brandy Grand Hoof right away because her hooves looked so perfect and sturdy. Then I saw that she was uncomfortable on our rocky ground. Although she cannot be ridden due to a medical problem, I was prepared to have her shod for comfort, but that turned out to be unnecessary – Grand Hoof was all she needed.

My horses have consumed so much Grand Hoof in the last 20 years that I have a wardrobe of shirts and vests from the rewards program. I’m wearing my favorite Grand Meadows vest in many of my book photos, including the one on the cover.

Q. You have a broad range of articles/videos on your website. Where should a new horse rider/owner start?

Lynn: I suggest starting with articles under the categories of Communication and Leadership or Horse Behavior and Herd Dynamics. The better we understand the thoughts and feelings behind horse behavior, the more successful we can be in building a partnership.

Q. What do you hope readers will take away from your book?

Lynn: There are concrete things we can do to create social bonds and provide the security horses want: use body language that invites horses to stay with us instead of move away, listen to their body language, encourage them to use their curiosity to overcome fear, build their confidence, and manage stress.

Q. What is one key message you want to share with horse owners?

Lynn: When horses feel safe with us there is less anxiety and fewer behavior problems. Instead we have confident partners who want to be with us.

Lynn’s book What Horses Really Want was published this spring and we’re pleased to provide you with an excerpt from her book.

Introduction to book excerpt: Wild horses live in social groups with close, long-term bonds that provide security. They spend most of their time roaming and foraging. Leadership is shared, aggression is rare, and rank is unimportant. Domestic lifestyles change everything. The resulting stress causes many behavior problems and explains many myths about horse behavior and herd dynamics.

The security of long-term social bonds is the exception for domestic horses. Many grow up without learning the social bonding skills to make positive connections with other horses, or to temper their own aggression or deflect that of others. The result is more aggressive behaviors, fewer social bonding behaviors. Even when they manage to make friends, those bonds are frequently severed because one horse is sold, moved, or switched to a different turnout arrangement.

Isolation often prevents horses from making social connections at all. Peering through bars at other horses is not social contact, and turnout in separate paddocks is a poor substitute for the physical closeness that provides security. The severity of the impact is shown in the fact that horses kept in stalls with little or no access to other horses are more likely to be aggressive toward humans.

Rank and Aggression

Rank is not typically determined by age, as in free-roaming bands. It is determined more often by “aggressiveness, temperament, or social experience.” Domestic living conditions often include the three factors most likely to cause aggression among horses:

- Confined spaces increase the likelihood that personal space will be invaded, a common cause of aggression.

- Having food supplied brings horses into close proximity, and invites guarding of resources. It is possibly the most significant source of aggression among domestic horses.

- Having food supplied brings horses into close proximity, and invites guarding of resources. It is possibly the most significant source of aggression among domestic horses.

It is no surprise, then, that domestic horses spend more time in aggressive behavior and less time in social bonding behavior than their free-roaming cousins. These higher levels of aggression explain why people unfamiliar with free-roaming herd behavior mistakenly believe that rank is important to horses and that aggression is a normal part of herd behavior. This makes it easy to overlook the importance of social bonds.

Other aspects of domestic living also contribute to stress, and potentially to aggression:

- Being confined is abnormal for horses. The less turnout time and space a horse has, the more likely he is to have behavior problems. When turnout is not possible, appropriate daily exercise is important for mental and physical health.

- Lack of opportunity to use curiosity and explore their surroundings makes horses more fearful and less adaptable to new situations. Fearful horses are clearly a common problem. Consider the prevalence of calming supplements for horses; the anxious horses and riders one sees at many events, and the great interest in “de-spooking,” “desensitizing,” or “bomb-proofing.” How many horses are sold or relegated to pasture-ornament status because their owners are afraid to ride them? Horses’ reactions to anxiety-producing situations are intensified when they are already stressed by their living situations and/or inappropriate diets.

- Diets high in carbohydrates and/or low in forage can contribute to stress-related behaviors and excitability. They are a risk factor for ulcers, which are found in 30% to 90% of domestic horses depending on the population studied. Such diets make horses more prone to aggression toward people, possibly as a result of gastric pain. Ulcers are rare or non-existent in free-roaming horses.

Leaders, Friends, and Social Networking

The shared leadership of free-roaming herds is based on a complex social network where horses decide whether to follow another horse based on their social bonds. Without these bonds, the system of leadership that is most natural for horses is not possible. Instead, a domestic social system may be a pecking order with rank determined by aggression. The highest-ranking horse may not be a leader any of the others would choose to follow, but a bully who has achieved rank through aggression while other horses do their best to appease or stay out of the way.

This excerpt from What Horses Really Want by Lynn Acton is reprinted with permission from Trafalgar Square Books (www.horseandriderbooks.com).

Buy Lynn’s book here: https://www.horseandriderbooks.com/product/WHHOWA.html